About a year ago I began this blog as one way to actively think about the path I was walking. For over 40 years I had walked a spiritually fulfilling path as a Christian, until realizing a couple of years ago that, somewhere along the line, I had stopped being a Christian and had become a Buddhist. Now I was walking an even more spiritually fulfilling path, though one far less familiar to me.

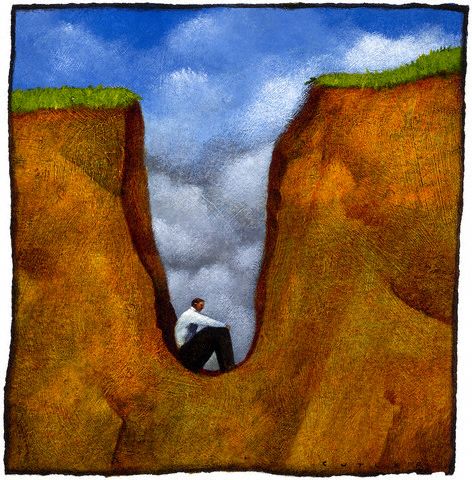

A lot of questions presented themselves to me and it seemed at times like I was feeling my way around in the dark. So I started blogging as part of my attempt to seek answers. It also occurred to me that I was probably not the only person seeking to answer those same questions. There might be a few people out there who would benefit from reading what I’m thinking, and it would be great to connect with those people and walk the path together.

Not long afterwards, I decided to create a page on Facebook with the same name, Dharma Beginner, as an extension of the blog and, primarily, to publicize its availability. My intention had been to post notices when new material was available on the blog, and perhaps the occasional quotation or link to a relevant online article. What happened next was wholly unexpected.

As of today, the Dharma Beginner page has 18,592 likes. That’s roughly 18,500 more likes that I would have predicted. So, an error of just 20109 percent, or slightly better than the accuracy of my NCAA basketball bracket.

This was not what I bargained for. This page has taken on a life of its own. In fact, I have been blogging only about once a month on average, but I am posting just about every day on the Facebook page. The regular visitors to the page seem to enjoy my blog but are obviously returning for other reasons given the infrequency of my blogging.

The regular visitors formed a beautiful little community right under my nose and without me noticing at first. Our virtual sangha, as I like to call it, has the same cast of characters as any in-person community. There are the gurus, as I think of them, the really experienced and knowledgeable people who can always be counted on to offer the perfectly apt quotation or to answer a baffling question. Thank goodness someone at the page knows something, because it’s not me!

There are the wallflowers who keep coming back but lurk in the corners, soaking up the experience while they shyly remain silent except for the occasional peep. Keep coming guys and gals and don’t feel pressured to speak up if you don’t want to. Just be there, because I love knowing that the page feeds you.

There are the hurt, those whose past experiences with organized religion have left them scarred and hypersensitive. My heart breaks for them and my compassion kicks into overdrive. I hope that they find some solace when they visit the page and are helped to recognize that happiness is within their grasp.

There are the debaters, ready to pounce on a point and beat it to a bloody pulp. I don’t know what I’d do without them, because they remind me that mine is not the only point of view and, quite often, their knowledge and passion puts me back in my place.

What there are, more than anything, are myriad people grateful for what they find at the page—which is amazing to me because I feel grateful for their presence. I am enriched by their many different voices and their common search for peace and happiness. I can’t imagine what my life would be like without them.

And this brought me up short recently. It began to dawn on me that I had a responsibility to the visitors to the page. I had been continuing my very low-key, minimally-responsible approach, posting the occasional quotation or article. But what happens when I go away, or simply am too busy to post? It doesn’t go unnoticed. People get worried about me. More importantly, people come looking for inspiration, a good word or two, encouragement, and see nothing new. I have given them a reason to expect such things, and sometimes I don’t deliver. Maybe they go away disappointed and never come back. Gosh, I hope not.

It occurs to me that, even though I can’t see the members of this community, it is a community nonetheless. One that I created and, therefore, am responsible for and to. If taking the Bodhisattva vows means that I have dedicated my life to aiding others in their search for enlightenment (and it does), then this is clearly one of the ways I have chosen to do so. Do I feel like I am upholding my vow in this regard? Not so much.

The issue has to do with much more than providing for new posts while I’m away on business or vacation, though. It has to do with taking risks, putting myself out there, and opening myself up to whatever may come. Just posting quotations and links to articles incurs very little risk. (Though, every time I refer to Chogyam Trungpa or Mother Theresa I set off a maelstrom! Can you say “polarizing individuals”?). My approach has been quite safe from criticism, quite safe from someone disagreeing or saying that I’m flat out wrong, quite safe from steering someone wrong and living with the consequences.

But more and more I find people reaching out for help publicly on the page and directly to me in private. Am I not responsible for helping them find an answer? I believe that, as the creator and maintainer of the page, I am. It is not a responsibility I sought, but I find that I am grateful for it and willing to embrace it.

I once heard one of my personal heroes and mentors, Bishop Walter Dennis, address a group of layreaders—people who read the Bible lessons to the congregation during church services. He emphasized the importance of preparation and taking the task of the layreader seriously by saying, “When you read the lessons, it may be the first time that someone has ever heard the scriptures, or it may be the last time they ever hear them because they will enter heaven before attending church again.” What an awesome responsibility! When it comes to this Facebook page, is it really any different? It could be the first time a visitor has ever read the Dharma or it could be the last time. Do I not owe it to them to provide something worthy of such occasions? I believe I do.

The denizens of Dharma Beginner may have noticed recently that my offering of quotations has come with some additional thoughts attached. That is me putting myself out there, expressing what the quotation says to me. That is me taking a little risk by exposing what I know and—more often—what I don’t know, opening myself up to disagreement, to the possibility that I will offend, to the chance that someone will read what I wrote and “unlike” the page, never to return. That would pain me indescribably, but I believe the potential gain, for the visitors and for me, to be far greater.

For a time now, I have been talking with my therapist about feeling called to do something different with my life, to set aside what I do now professionally in order to pursue a career helping other people spiritually. It’s a scary proposition: I’m very good at what I do now (as a researcher and author on government finance), I’m respected and well-known nationally within my particular industry, and I make a decent living. I have no idea if I’d be any good at being an author and speaker on spiritual matters, or whether I could support myself and my family doing so. So I’ve decided to take a small step in that direction, a toe dipped in the water, and the Dharma Beginner page is the base of operations from which I’m going to start doing that. I’ve been using the Twitter account associated with the page (@dharmabeginner) more often. I’m thinking about writing some things to submit to other web pages and magazines. I hope you’ll stick with me and continue to lend me your thoughts and opinions and support and friendship. Because it means so very much to me, and because I am so very grateful for it. Thank you.